Famous Views of Japan

Among the most popular subjects in Ukiyo-e were the views of famous places (*meisho*) in the capitals and provinces across Japan.

Hokusai's series from the 1830s, such as *Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji*, *A Journey to the Waterfalls of Japan*, and *Unusual Views of Famous Japanese Bridges from All Provinces*, represent the pinnacle of this genre both for their graphic originality and innovative use of polychromy.

The application of Prussian blue, and the creation of prints using only this colour—imported to Japan from Germany at that time—along with the assimilation of Western perspective, reflect the contemporaneity of this artistic trend.

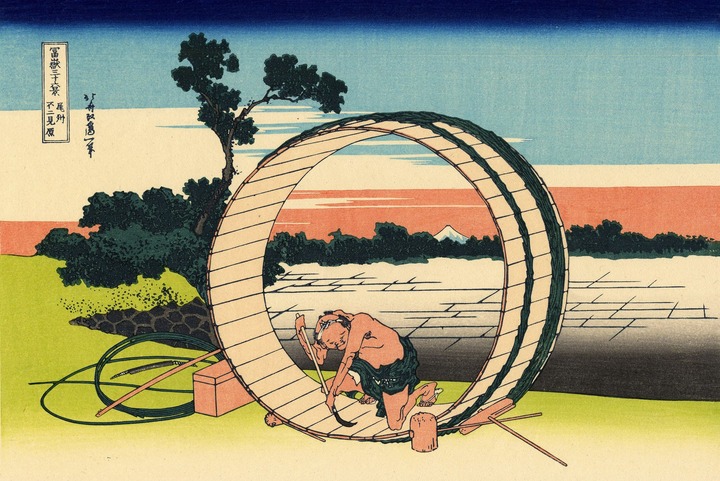

Tenma Bridge in Settsu Province (Settsu Tenmabashi)

from the series: Unusual Views of Famous Japanese Bridges in Various Provinces (Shokoku meikyō kiran)

Katsushika Hokusai,

1833-1834

Polychrome woodblock print (nishiki-e)

From the Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

©Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

These places were often already known through poetry and classical literature, associated with natural and seasonal features like waterfalls, cherry blossoms, or the reddening of maple trees.

They had also become attractive due to events, performances, or the presence of structures such as bridges, temples, shrines, inns, restaurants, and shops that had sprung up in cities and along the new roads.

In addition to individual prints, illustrated books (*ehon*) helped popularise Edo (Azuma) and the Tōkaidō Road as well as other famous locations.

View of Fuji from Fujimigahara in Owari Province (Bishū Fujimigahara)

from the series: Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei)

Katsushika Hokusai,

1830-1832

Polychrome woodblock print (nishiki-e)

From the Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

©Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

Views of Mount Fuji

The most famous and iconic of all “meisho” views is that of Mount Fuji, a subject no artist could resist.

Over the centuries, hundreds of works have been dedicated to it, from painted scrolls and polychrome woodblock prints of every size and quality, to pages in books and monographs.

Fuji is not only Japan’s highest volcanic mountain, but it is also considered the sacred abode of the gods according to Shinto religious thought.

During the Edo period, a popular cult developed, encouraging pilgrimages to the mountain and even the construction of small Fujis within cities for those unable to visit in person.

Hokusai was undoubtedly a devotee of this place, which became the subject of his most significant works: the polychrome series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” created between 1830-32, consisting of 46 prints, including the famous “Great Wave” and “Red Fuji”;

and the three beautiful volumes of “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji” printed in black ink in 1834, which open with the figure of the goddess of the mountain, Konohanasakuya-hime no Mikoto, and contain Hokusai’s artistic testament, signed "Manji, the old man mad about painting".

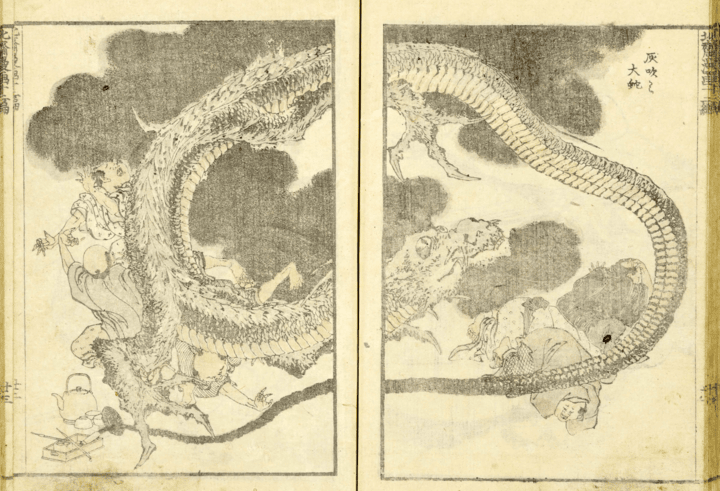

Manga and Manuals

The Manga, literally "Hokusai’s Random Sketches: Education of Beginners through the Spirit of Things", consists of fifteen volumes published in black ink with only a few touches of pink, starting in 1814 and concluded after Hokusai’s death with the fifteenth volume in 1878.

They symbolise the master's enormous production of manuals.

From the 1810s to the 1819s, Hokusai, using the art name Taito, produced manuals offering designs of classic subjects like birds and flowers (kachōga); decorative patterns for artisans working in textiles, lacquer, ceramics, and metal, such as the “Illustration of a Thousand Trades”;

and drawing manuals teaching how to quickly sketch various figures, like the “Collection of Rapid Drawings of Mountains, Water, Flowers, and Birds”.

His manuals on colour, dance, warriors, and legendary heroes, like the Chinese bandits from Suikogaiden and the “Illustrated Books of Samurai”, aimed to provide guidance for his many students and anyone wishing to learn painting.

The pages of tiny sketches and double-page drawings in the Manga form an encyclopaedia of life and creation, summarising the studies found in Hokusai’s polychrome prints.

They also served as a major source of inspiration for Parisian Impressionist artists.

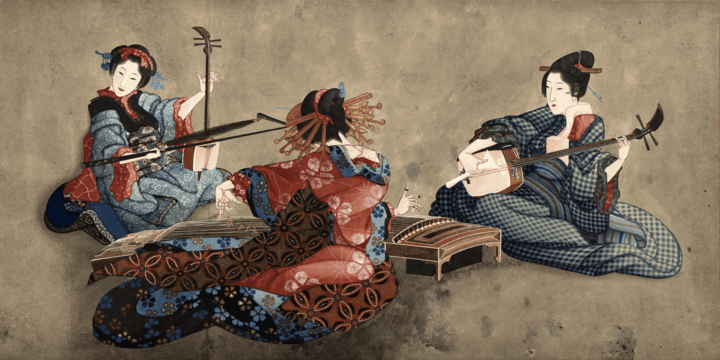

Shunga

Shunga, literally “spring images”, refers to erotic images that, despite being a secure source of income for all artists, circulated covertly to evade government censorship.

These were polychrome prints sold in sets of loose sheets, bound in albums of twelve, or found in illustrated books and painted scrolls, sometimes for display or for private viewing.

They were even given as dowries to young women.

Among Hokusai’s most beautiful illustrated books and albums are the three volumes “Love Spasms” (Kinoe no komatsu) from 1814, famous for the amorous image of the pearl diver and the giant octopus, and the album “Plovers on the Waves” (Nami chidori) from around 1810-1819, continuously reprinted with different colours.

Monumental, intertwined bodies, engaged in romantic or secretive, sought-after or unfaithful, heterosexual or homosexual acts, fill the sheets, with exaggerated and prominently displayed genitalia.

Representations of Poets and Poems

Classical poetry anthologies were a major source of inspiration for Ukiyo-e artists.

Under the art name Manji, Hokusai produced two series of polychrome prints aimed at the mass market: one, in a vertical nagaban format, titled “Mirror of Japanese and Chinese Poets” (1833-34); and a second in the classic horizontal format, “One Hundred Poems for One Hundred Poets in Illustrated Tales of the Nurse” (1835-36).

The former features ten portraits of Chinese and Japanese poets who shaped classical poetry, with landscapes evoking their verses and native places, executed in a vertical composition that exudes poetic grandeur.

Sangi Hitoshi (also Minamoto no Hitoshi) (Sangi Hitoshi)

From the series: One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, Explained by the Nurse (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki)

Katsushika Hokusai,

1835-1836

Polychrome woodblock print

From the Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

©Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

The latter series, drawing from Fujiwara Teika’s 1235 anthology “One Hundred Poems for One Hundred Poets”, portrays vivid scenes in shades of green, brown, red, blue, and yellow, but remains incomplete with only twenty-seven finished prints and around sixty-four preparatory drawings (shitae).

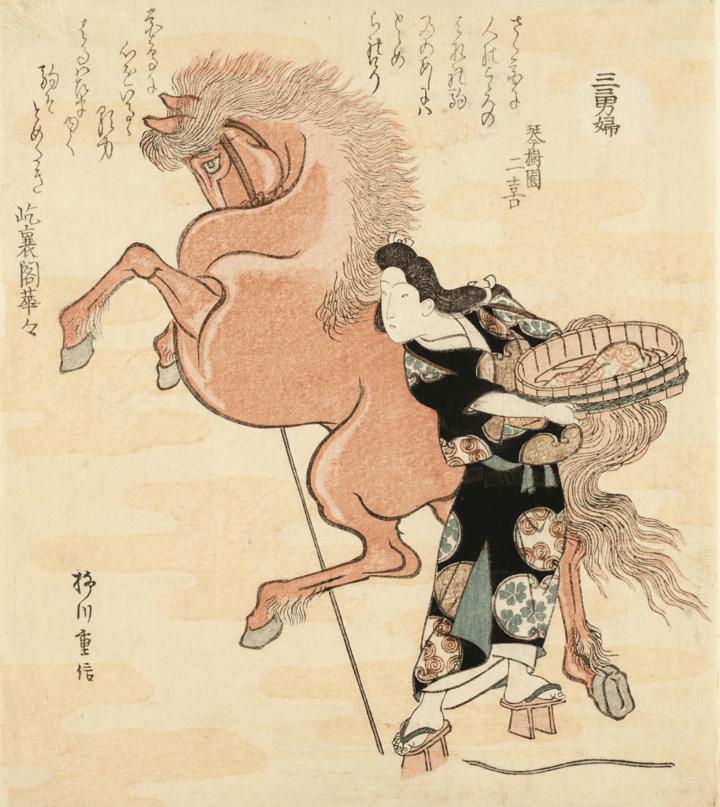

Surimono

Surimono (literally "printed things") represent the most refined and culturally elevated Ukiyo-e production, created for a small, private clientele.

These were greeting and commemorative cards, calendars, announcements, and invitations, mostly exchanged within kyōka and haikai poetry circles, especially at New Year’s.

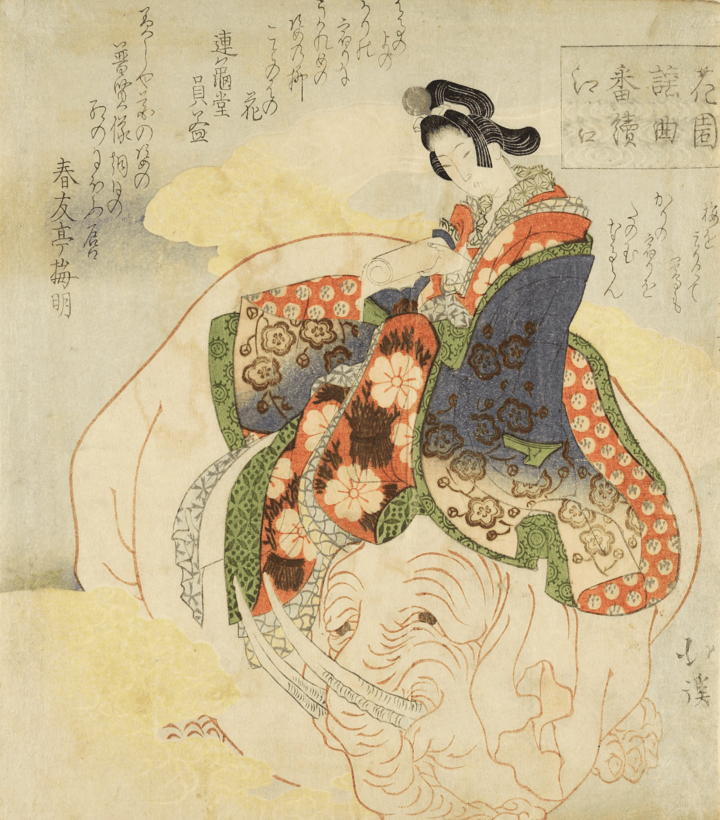

Series of Nō Performances for the Hanazono Club (Hanazono yōkyoku ban tsuzuki Eguchi)

Totoya Hokkei

1820

Polychrome woodblock print (nishiki-e), silver metallic pigment, with embossing (karazuri)

From the Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

©Museo d'Arte Orientale Edoardo Chiossone, Genova

Printed in various formats, they combine polychrome printing with Ukiyo-e artistry and renowned poets’ verses or prose to complement the print's subject and meaning.

Unlike the polychrome prints, surimono feature subjects tied to classics, folklore, mythology, and traditional festivals, with meticulous attention to detail, incorporating costly materials like metallic powders and blind embossing techniques.

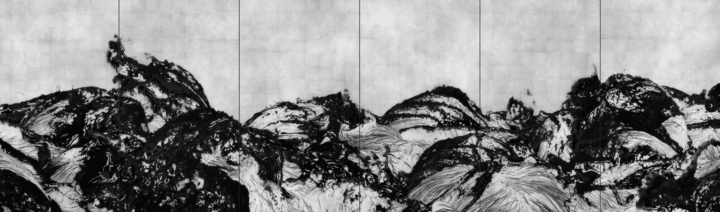

Hokusai as Painter

In the paintings made by Hokusai using brush strokes on paper and silk, one enjoys the full freedom of expression and his sensitivity to materials, colour and line without the mediation of the engraving work present in the prints.

One can read the evolution of the sign, the continuous change in the treatment of his subjects.

In the paintings of beaux-arts there is, from the 1910s and for the first decades of the 19th century, a transition from flowing, soft lines to more broken lines, from slimmer, longer figures to more imposing one's.

The singular portrait of a woman giving birth made during the Taito period with a realist approach dates from 1817.

As he grew older, he devoted himself to more spiritual and auspicious subjects that were meant to accompany and protect him: divine and legendary animals such as Chinese lions, tigers combined with the bamboo plant, carps and turtles thousands of years old, and dragons ascending to Fuji and the sky.

The dragon was the sign of the zodiac under which Hokusai was born and under which, at the age of sixty, he decided to leave his stage name Taito to his pupil who became Taito II.

Accompanying Hokusai until the end of his life was his daughter Ōi, also a talented painter, who collaborated constantly with her father, working four-handed and whose skill in the Western painting technique of chiaroscuro can be admired.

Japanisms

Together with that of Utamaro and Hiroshige, it was Hokusai's work that offered the greatest creative inspiration to the European artists and intellectuals of the 19th century who initiated the Japonisme movement.

Impressionists and post-impressionists found in his prints and the pages of his manga and manuals not only exotic subjects to collect and exhibit in private, but an innovative approach to line, colour and image construction that overturned all the pictorial canons hitherto achieved, allowing a new freedom of expression.

A source of inspiration that never lost its grip.

On the contrary, it could be said that Hokusai's work shows all the primordial characteristics of contemporary developments as witnessed by the citations and revisitations of the master's iconic works by the most important contemporary pop, graphic and digital artists such as Yoshitomo Nara, Manabu Ikeda, teamLab and Simone Legno /Tokidoki.

The application of new technologies and materials has further fostered the exploitation of the graphic power of ukiyoe prints, reaffirming the originality of this artistic strand and Hokusai as the greatest exponent of a new Japanism.

![South Wind, Clear Sky [Red Fuji] (Gaifū kaisei) South Wind, Clear Sky [Red Fuji] (Gaifū kaisei)](/data/uploads/images/sezioni-mostra/2-2-Giornata-limpida-con-vento-del-sud-[Fuji Rosso].jpg)